41. ✷ From Dissertation to Diapers

We figured there wasn’t much else to having a baby. After all, I slept in a dresser drawer at first, so this definitely was an upgrade.

First things first

Our first purchase was a huge desk with a laminated wood top and chrome legs for the second bedroom. The expansive surface was wide enough for the pesky unfinished dissertation to perch on one side, while Jim’s class preparations and institute projects took up the rest. In front of it, we squeezed a second-hand blond crib, adorned with the teeth marks of its four previous occupants, the Conant children. The arrangement reminded me of the long-ago Washington D.C. dining room where Lynne’s crib had shared a small space with the mahogany dining table. We figured there wasn’t much else to having a baby. After all, I slept in a dresser drawer at first, so this definitely was an upgrade. There seemed little else to do but wait.

On July 20, 1971, I wrote in my journal:

“Summer is upon us… interminable. The world reflects my own restlessness what will really become of me now that I have set aside one career, well defined, for another, not defined at all? Am I strong enough to be creative, curious, eager for each day — without a pre-designated series of challenges? I dream of writing, but wonder how much I have to say. I dream of art projects — warm, friendly things — and wonder if my imagination can take me there. I wonder about a baby, the mystery of it all… The change from daughter to mother — what a giant step! Is my stride long enough?”

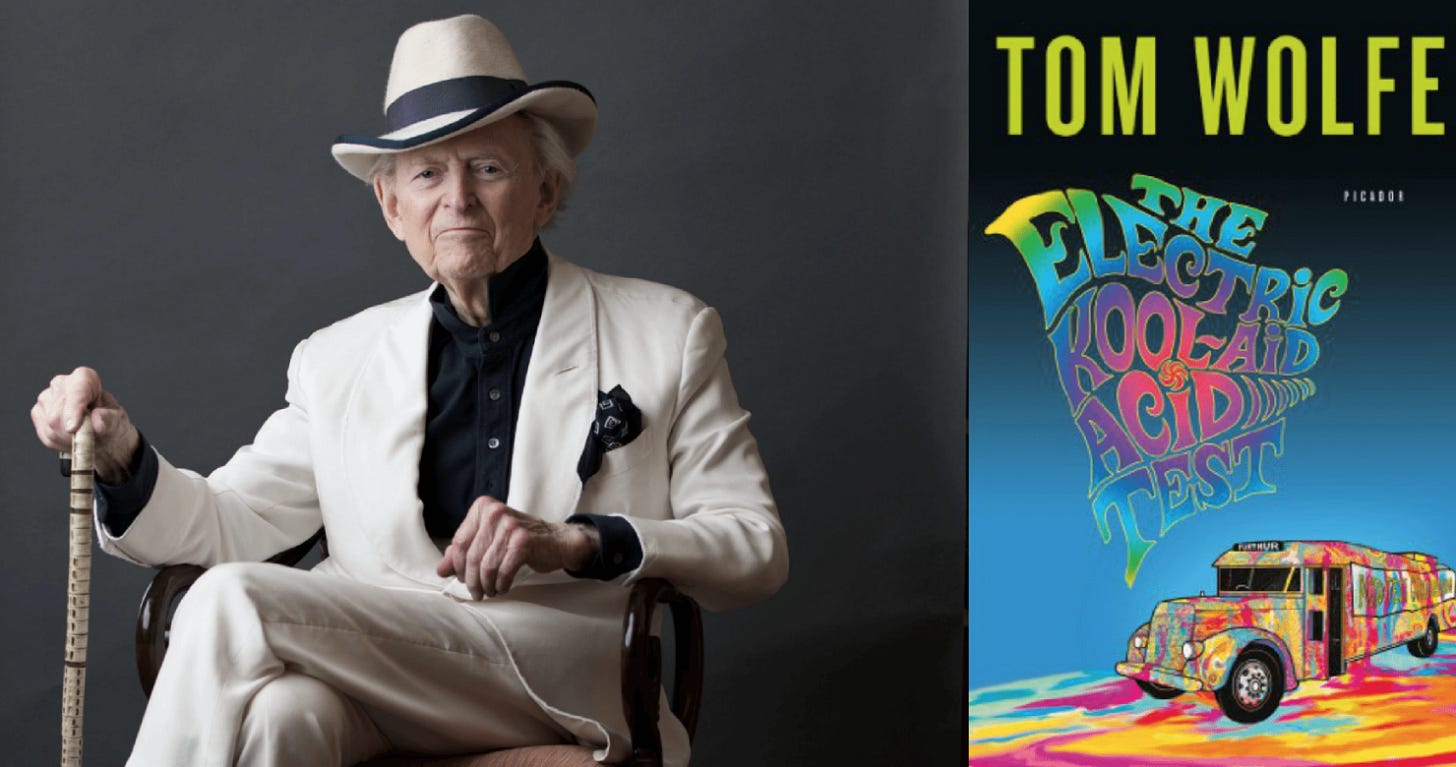

I mulled over those questions and others as I explored. Eugene is the second-largest city in Oregon. On nearly every measure, compared to Los Angeles, it was something of a parochial monoculture, notably in that it was overwhelmingly Caucasian, with only two large employers — Sacred Heart Hospital, where both children would be born, and the University of Oregon itself. Today, the city’s website describes it as having a “large, though aging, hippie population.” That was an apt description in 1971, as well (minus the “aging”). During the late afternoon, mild fall days, I would often walk the 30 blocks to Jim’s office. We decorated it with brown and yellow curtains and a Marimekko orange, gray and rust stretched fabric with the Golden Gate Bridge sweeping across it. The walk passed many ramshackle houses with psychedelic vans parked either in front or askew on what had once been lawns. It looked like a tapestry saluting Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters. Kesey, author of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and the male protagonist in “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test,” still remains central to Eugene’s identity. On Saturdays, we sometimes shopped at Grower’s Market, near the downtown train station. It is the only food co-op in the United States with no employees.

Anticipation

That first fall was a time of watching and waiting. I outgrew my clothes and bought several maternity tops and one maternity dress. Although it was an attractive red plaid, I quickly learned that if you only have one dress, it shouldn’t be plaid. By the time Geoff was born, I vowed never to wear plaid again. It took 25 years before a handsome blue and green skirt finally tempted me enough to buy anything remotely resembling a cross-barred pattern. I had never babysat or spent any time around young children, except Lynne (whom I studiously ignored most of the time). I began watching all kinds of mothers — tall and small, hippie and well-groomed, wives of blue-collar workers and professional men; mothers with babies in the park, the grocery store, the doctor’s office. I would think to myself, “That mother is too cross, or is letting her child misbehave, or isn’t paying attention. I certainly will never do THAT.”

Kahlil Gibran was right: “Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of life’s longing for itself. They live in a land you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.”

You have to be a parent yourself to realize how obtuse those observations were. Being a parent is nothing if not humbling. Most mothers are paying attention even when they look like they aren’t. Being exhausted makes people cross, and children sometimes misbehave despite the best efforts of their parents.

The first months of teaching were extremely trying for Jim. Preparing classes he had never taught, working in the IR Institute, and trying to keep his dissertation committee focused were huge challenges. I had my own problems. On October 4, 1971, I wrote:

“We have begun. A new life is upon us — far from palm trees, California freeways, smog, the groans of a giant city, and its familiar faces. The challenge of the here and now is no small force to reckon with. How does one make new friends without degenerating into the “coffee-every-day-until twelve” routine? All the prospects for growth here seem confusing — which way to turn without becoming “Mrs. Suburbia clubwoman”? Time will be the final judge of the wisdom of the present decisions.”

Casting about for something more positive, I ended by saying, “The beauty of Oregon lies in the natural wonders around. Even our service station looks friendlier doing its job amid the trees. Despite the anxiety, there is a tranquility here.” The landscape might have been tranquil, but we weren’t.

At night, Jim would study at the big desk, with its spindly legs and high back swivel chair, and I would read. Three books occupied the fall. First, I read Benjamin Spock’s “Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care.” My mother recommended it. It was the only book on child-rearing she had used. I figured Lynne and I turned out okay, so that was good enough for me. Mother wasn’t the only one. Dr. Spock’s manual sold over 50 million copies and has been translated into 39 languages. In contrast to parenting manuals before his 1946 book, his message was revolutionary. Simply, parents know more than they think they do. Be flexible. Pick babies up when they cry. Feed them when they are hungry, not on a predetermined schedule. His ideas empowered parents, including us. Ultimately, Spock was blamed by everyone from Norman Vincent Peale to Spiro Agnew for creating “two generations of permissive parenting,” which many people felt had led to every social ill of the 1960s. Nothing like looking for easy answers to complicated problems. Some things never change.

Next, I read Irving Stone’s powerful biography of Michelangelo, “The Agony and the Ecstasy.” It is the story of the artist’s lifelong titanic struggle to release the forms and beauty imprisoned in pure white marble. It seemed like parenting might be the same. Eventually, I realized the metaphor was exactly backwards. Parents don’t carve children into static images. The best ones nudge gently, but let children become who they were right from the outset. Kahlil Gibran was right: “Your children are not your children. They are the sons and daughters of life’s longing for itself. They live in a land you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.”

Finally, I read the “Great Lion of God” by Taylor Caldwell. It is the moving story of the life of Saint Paul, one of the most passionate and dedicated of the Apostles of early Christianity. He had more influence on the Western world than people know. The Christianity he spread is the bedrock of modern jurisprudence, morals and philosophy. Above all, the ideals of liberty — of mind, body and soul that Judeo-Christianity embodies — were a new concept among men. In the recent presidential campaign, now President Obama often said, to great cheers, that America is no longer a Christian nation. More people identify themselves as spiritual but not religious, agnostic or atheist than ever before. While Christianity appears in decline, the loss may be greater than any of us can ultimately imagine. Discussing this recently with Don Dodson, the scholarly Vice Provost at Santa Clara, he had the same feeling. “People might do well to study the history of Spain,” he remarked.

I remember Ronald Reagan broaching the topic of a Judeo-Christian God with Mikhail Gorbachev. Some observers felt it was just a negotiating ploy designed to deflect attention from more substantive issues. It seems more likely that President Reagan was raising belief in God out of personal conviction or out of a fundamental understanding of the atheist record of carnage in the 20th century, particularly in the Soviet Union. More than 100 million deaths can be attributed to the atheist regimes of Stalin, Hitler and Mao. As Dinesh D’Souza points out in his book “What’s So Great About Christianity,” all of the deaths attributable to Judeo-Christian zealots in the Crusades, the Inquisition and witch burnings, however reprehensible they were, amounted to approximately 200,000 over a period of many centuries. From a purely statistical standpoint, the odds of surviving under a leader who believes in a Judeo-Christian God are much better by a factor of at least 500 to 1. Ronald Reagan got many things wrong — among them, closing mental health facilities, deficit spending — but on this issue, he had a point. More recently, Darfur, Rwanda, Zimbabwe and the Khmer Rouge, all starkly reinforce the idea that a godless world is an untenable one.

Hahaha -- I slept in a dresser drawer, too! I wonder how many babies have done this.